David O' Riordan beszámolója.

The appearance of world-renowned Italian baton-dangler, Riccardo Chailly, helming the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, at the National Concert Hall in Budapest last Friday, has been one of the more vigorously trumpeted events of the concert season, with Chailly's strangely evocative bearded face – it reminds me, personally, of wooden panelling found on certain living room floors – looking down from many a billboard around the city. The versatile conductor – just as comfortable in bed with Beethoven and Mahler, as he is with Italian opera and 20th century atonal avant-garde – doubtless was a natural draw for the more tarty of Hungarian concertgoers, in attendance more due to the dazzle of his celebrity, than because of the pieces being performed.

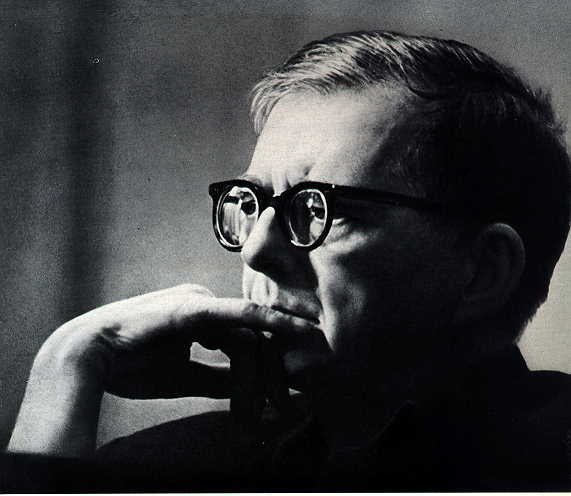

The concert began with a performance of Shostakovich's first Violin Concerto. The work originates from around 1948, though its premiere was held back till 1955, presumably because Shostakovich feared that Stalin would use him as part of the ingredients in a savoury pie, if he ever heard it. (The late 40s were a time of particularly severe censorship in the Soviet Union, manifested in the Zhdanov Doctrine, attacking “formalism” in music.) For all the merits of the introspective first movement – with its delicious, otherworldly harp chord some ten minutes in – and the Disneyland-meets-Gone with the Wind derangement of the Scherzo – “Frankly, my dear, I don't give a rollercoaster mickey mouse...” – the centrepiece of the concerto is the third movement, the Passacaglia, one of the most achingly beautiful and melancholy pieces in Shostakovich's entire oeuvre. This is presumably also Chailly's view, for the movement was preceded by a protracted, solemn pause, either because he genuinely had to prepare himself emotionally, or merely because he thought this would achieve pathos for the audience. What followed was not bathetic – there was no post-pathos bathos – but the tempo, nevertheless, did seem a little rushed. However, the soloist, Leonadisz Kavalosz, came into his own during the lengthy Cadenza, showing no timidity in the more percussive, abrasive passages, each slash of the violin bow bringing to mind the horror of a cancer-ridden pregnant widow in Siberia, about to give birth to a baby with a wolf's mouth. This segued exhilaratingly into the finale, with the orchestra's sudden return, led by an unhinged xylophone riff, evoking an image of Stalin gaily and boisterously dancing with a cute pig-tailed school girl in a shed, during which he absent-mindedly knocks over a snuff box.

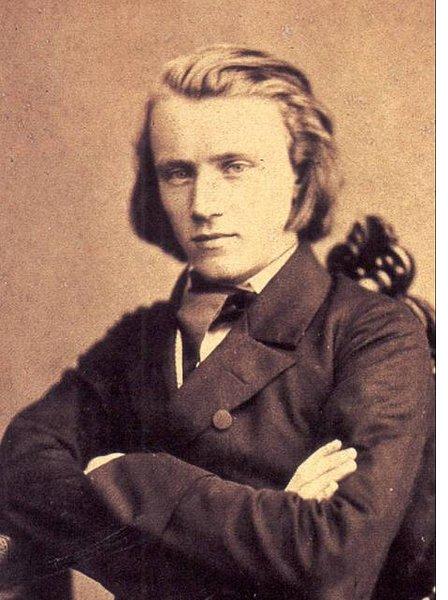

One feature of the National Concert Hall is the availability of boiled sweets outside the hall, both before the concert and during the interval. This led, on this night, to a not especially exciting but nonetheless noteworthy incident during the main event, a performance of Brahms' third symphony. During the third movement, an elegantly-dressed – but perhaps philistine? – woman was unwrapping one of the sweets – an invariably loud and somewhat protracted procedure – causing a long-haired, bearded middle-aged man, sitting in the row ahead of her, to look back indignantly, and make various facial expressions and hand gestures, conveying that she ought to stop this right now. As it happens, Brahms' third symphony – at least for me – generally maintains a tone of genteel quiescence, with the third movement possessing an ever slightly greater hint of dread than the rest of it. As such, it served as a perfect complement to the low-level boiled sweet conflict. No such congruity between music and audience atmosphere was achieved during the Shostakovich performance, which is fortunate, for that would have required the butchery of an untold number of innocents.

The symphony itself is a work I find pleasant but not greatly engaging – thus, I wasn't especially pedantic about Chailly's trea tment of it. As stated, however, the symphony does have an appealing pastoral calm to it, allowing one to daydream, during a given performance, about buttered scones and cardigans, and kindly grandmothers, and potted plants on delightful sunny spring afternoons; and the aforementioned kindly grandmothers smiling at children playing in a beautiful park, in which there is a deeply aesthetically-pleasing fountain; and young pretty girls in frilly dresses using foul language, thus signifying the collapse of society, also exemplified by declining church attendance. Insofar as I was able to envision at least a portion of the above, Chailly's performance was a success.

tment of it. As stated, however, the symphony does have an appealing pastoral calm to it, allowing one to daydream, during a given performance, about buttered scones and cardigans, and kindly grandmothers, and potted plants on delightful sunny spring afternoons; and the aforementioned kindly grandmothers smiling at children playing in a beautiful park, in which there is a deeply aesthetically-pleasing fountain; and young pretty girls in frilly dresses using foul language, thus signifying the collapse of society, also exemplified by declining church attendance. Insofar as I was able to envision at least a portion of the above, Chailly's performance was a success.

Come the time of the encore, I was half-heartedly hoping that Chailly might give us, say, the entirety of Mahler 9, just for fun, but alas that didn't happen. Instead, it was Brahms' more modest Academic Festival Overture. When it ended, keeping in mind Chailly's reputation for introversion, I didn't see much point in forcing my way in backstage, and persuading him to join me for a few pear palinkas, in a dive bar near Blaha Lujza ter. Nevertheless, I can still cling to the dream that future circumstances will enable this to happen.

2012. május 18.

Bartók Béla Nemzeti Hangversenyterem

Sosztakovics: I. (a-moll) hegedűverseny, op. 77

Brahms: III. (F-dúr) szimfónia, op. 90

Közreműködik: Leonidasz Kavakosz – hegedű

(A képek illusztrációk.)